Warranties

• Interpretation of warranty is best left to Merriam-Webster: ". . . written guarantee of the integrity of a product and of the maker's responsibility for the repair or replacement of defective parts." Generally speaking the manufacturers are sincere and cooperative about repairing or replacing any items which function improperly or fail because of material, design, construction or assembly. Distributors see the warranty as a way to encourage retail buyers. Generous warranty coverage policies are intended to reflect the distributors' confidence in their products' quality and durability.

Motorcycle dealers, on the other hand, usually view warranty as a necessary evil. A component failure requires the manufacturer to supply the part, the distributor to cover the labor cost and the customer to deliver the motorcycle to the dealer's doorstep. But the dealer has to do all the dirty work—fill out forms, discover the failure's cause, repair and replace any broken parts. The dealer also has the most difficult task of all-dealing with irate owners. It is a fact that dealers do not make money on warranty work; unless they are fudging the paper work they are fortunate to break even.

As soon as you put down your hard cash for a new motorcycle you have become the most important party in the warranty chain. It is the customer's responsibility to have the motorcycle properly cared for and serviced. As long as the motorcycle is not misused, raced, crashed or neglected, and recommended service procedures and products are used, the owner is entitled to full parts and labor coverage for any product failure (within the prescribed warranty period) due to faulty material, design, construction or assembly.

It is our experience that dealers are extremely cautious, often cold, when dealing with customers' warranty claims. A lot of customers try to stiff dealers with borderline or fraudulent claims for any one of a million reasons. Just as commonly, dealers will shirk their responsibilities in warranty cases.

|

WARRANTY TERMS

|

HONDA CB550F CB500T

|

KAWASAKI KH400

|

SUZUKI GT550 GT380

|

YAMAHA XS500C RD400C

|

|

Miles |

6000 |

No Limit |

4000 |

4000 |

|

Time |

6 Mos. |

6 Mos. |

6 Mos. |

6 Mos. |

|

Warranty |

1 to 3 Mos. 1 |

3 or 6 Mos. 2 |

12,000mi./ 12 Mos. 3 |

None |

|

Extension |

None |

$25 or $40 |

None |

NA |

|

Service Required By:

|

Dealer or owner

|

Dealer or approved mechanic |

Dealer only

|

Dealer or owner

|

|

Transferable Warranty |

No |

Yes |

Yes 4 |

Yes |

|

Towing Charge Allowance |

None |

None |

None |

None |

|

Coverage Within:

|

U.S.A Canada Puerto Rico Virgin Isles |

U.S.A.* Canada Puerto Rico Virgin Isles |

U.S.A. only |

U.S.A. only |

|

*Excluding Hawaii |

|

|

|

|

It is best to approach a dealer with calm accuracy regarding any warranty situation. Expect to explain completely the details surrounding your motorcycle's problem. An ounce of courtesy will be worth a ton of help when confronting the dealer's personnel. An irate customer will, as often as not, receive the same courtesy (or lack of it) as he presents to the deafer.

Basically, Honda, Kawasaki, Suzuki and Yamaha have the same warranty coverage plans for their motorcycles. Each has a different period of mileage and/or time during which the policy remains in effect, but will cover 100% of the parts and labor for the period specified in the owner’s manual. All are specific about the parts and labor coverage, including only the warranty-related repairs or parts replacement. And all list the servicing procedures and mileages at which they must be performed.

Each manufacturer can void the warranty coverage as follows: the prescribed servicing has not been performed; the motorcycle has been used for racing; the machine has been abused or used in an unspecified manner; a warranty-related problem has been caused by unauthorized service or repair; installation of non-factory parts or accessories have led to a failure, handling deficiency, modification or weight exceeding the gross vehicle weight limit; or the prescribed time or mileage for warranty coverage has been exceeded.

There are simple dos and don'ts to follow in keeping your warranty valid—in extreme cases, past limits of time and mileage. Follow the service recommendations. Honda, Kawasaki and Yamaha do not require this servicing to be done by one of their dealers—although it is probably best to do so. If an owner does his own servicing he should keep receipts of all the supplies used (lubricants, spark plugs, etc.) and fill out and date the check-off lists in the handbook. These can be shown to the dealer as evidence that servicing has been accomplished at the prescribed times with approved products. Suzuki requires servicing from an authorized dealer at designated mileages. A full record of receipts will assure complete coverage-especially at an out-of-town dealership.

A customer can save labor expenses by doing his own servicing, but it's a good idea to have the first and last servicing done by a proper dealer. Not uncommonly, he may discover an impending problem area which an inexperienced customer might not be aware of prior to failure. A good dealer will correct any warranty-related problem for you before your bike's warranty expires and charge the factory—not you. If you can strike up a relationship with your dealer's service personnel they will often alert you to parts or areas prone to sporadic failures.

Honda's warranty policy is most specific about voiding coverage by installing non-factory parts. Check with your dealer before mounting a fairing, saddlebags, rack, etc. to see the possible ramifications of any non-factory accessories. They also offer warranty time extensions for those who purchase a Honda in the off-season months.

Overall Results

1. Suzuki GT550 .. 6.52

2. Honda CB550F ..6.07

3. Suzuki GT380 .5.75

4. Yamaha RD400C 5.68

5 Yamaha XS500C..... ..5.62

6. Kawasaki KH400 .. 4.30

7. Honda CB500T .. 2.82

Conclusion

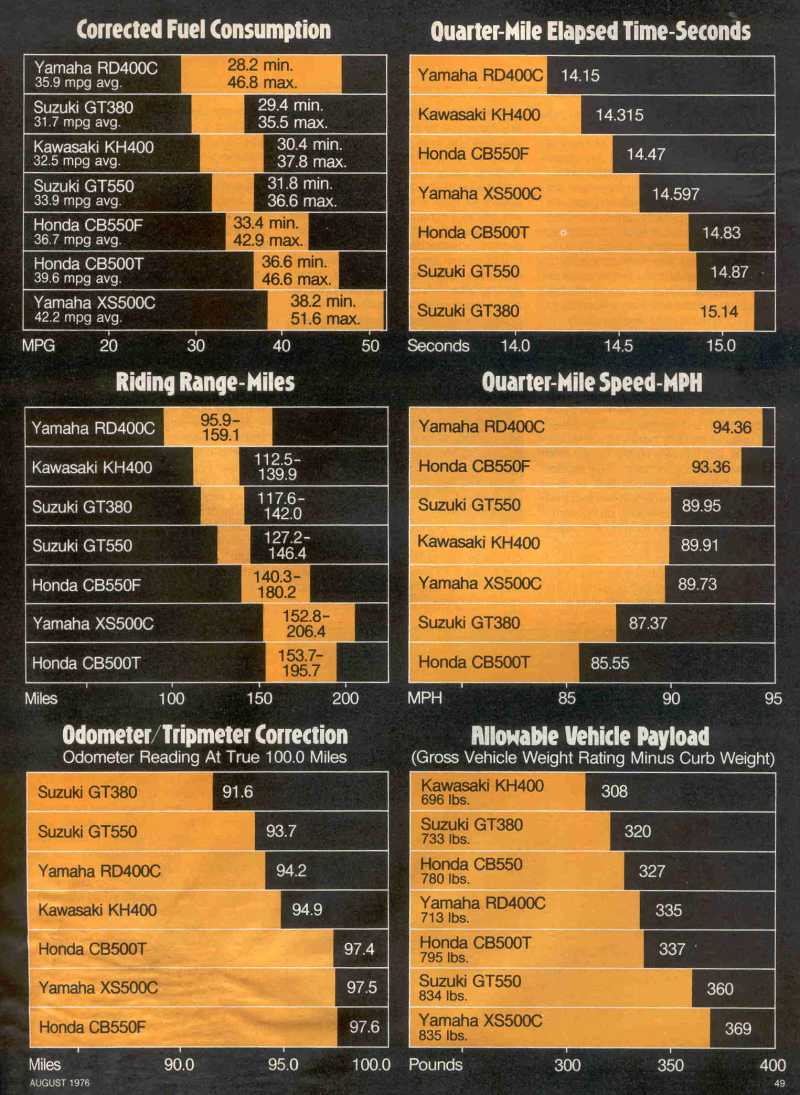

• With three first-place category wins, three seconds, a third and a sixth, the Suzuki GT550 is the unchallenged winner of our Middleweight Comparison test. It had the best engine, was judged the most comfortable, was the easiest to manage around town and finished second in the Fit and Feel, Noise Control and Vibration Control categories. Beyond the addition and division of point totals the Suzuki was the bike that most of the testers liked the best. (Six out of seven riders said they'd buy a Suzuki 550 if they were in the market for a touring middleweight.) Despite the fact that the 550 has been subjected to minimal development work since its introduction four model-years ago, it has a agreeable texture which suggests that the design team got it right the first time, and has had the good sense to leave it alone.

The only element of the 550's character we weren't thrilled with was its lack of cornering clearance. With its steam-calliope exhaust complex tucked up and in, the 550 would be as close to a perfect motorcycle as anyone could ask for.

The Honda CB550F finished a half-point below the bigger Suzuki and in unthreatened possession of second place. Make no mistake: the Four is a super-scooter. It's beautifully assembled, quiet, fast and subtle, and its engine gives it the ability to do a wide range of motorcycle-y things with brilliance—like win production races (the GT550 can't), get good mileage and produce an enchanting sound from the end of its muffler. But to match the GT550 in the comfort categories the bike needs a lighter throttle, a more compliant suspension and a more carefully thought-out relationship between seat, pegs and handlebar. And while it was better on twisting roads than the GT550, it wasn't enough better to offset the Suzuki's advantages in other areas of evaluation.

The Suzuki GT380 finished an astonishing third overall, despite a rating of "tolerable" in the engine performance category (3.71) and the worst fuel consumption problem of all bikes tested (31.7 mpg average). The 380 scored well for the same reasons the GT550 did—it's comfortable, willing to work, unobtrusive and eager to please, and the impression it imparted to everyone who rode it was one of solidarity and charming toughness. It's stone-slow compared to the class's rocket ships and it's dawg-meat in the mountains, but its commanding presence in the categories having to do with pleasant traveling jolted it up high in the standings. The 380 finished ahead of the RD400C, which surprised nobody more than us. The RD does brilliantly what it does well: flick through the mountains (it won that category by a half-point), get up on its pipe and haul ass, and tip-toe around town. Its suspension compliance was rated second only to the XS-500C's, and its engine is more than acceptably smooth for a twin. Would the testers buy it for tearing around? Six said yes, and one said yes if he were 50 Ibs. lighter. How about for touring? All seven said no—and that's what dropped it to fourth.

In fifth place, the Yamaha XS500C, a bike that's almost there, but not quite. Those of us who remember last year's version are impressed with the progress Yamaha has made in quelling the bike's drive-line snatch, and there's no doubt about the stability of the XS's chassis and the category-winning compliance of its suspension system. But it'll still over-react to variations in throttle opening, its engine performance was not thought to be beyond improvement and it could be easier to ride through town.

The Kawasaki KH400 slotted into sixth, which is a ranking that surprised no one. It gobbles gas, growls through its intake manifold, bounces down the Interstate and transmits a goodly amount of engine-buzz. But . . . but. It sure is fun to ride under the proper circumstances. It accelerates quickly, has terrific cornering clearance, a nice front brake and a stable chassis, and it doesn't cost much money. If you buy it for the right reasons, it'll delight you with its better-than-good handling and its anxious little engine.

The Honda CB500T finished last, 2 1/2 full points behind the sixth-place bike, and we feel almost like apologizing for including it in the first place. If you've read this far you know why, so a rehearsal of its shortcomings is unnecessary. We think it's time for Honda to put this bike out of our misery. It was an inspired creation in 1966 and it reached comparative perfection in 1971, but other middleweights have been lapping it ever since. The longer Honda persists with it the worse it's going to get—even if it stays the same.