Motorcycle Enthusiast

KAWASAKI MACH III

SAINT OR

SINNER?

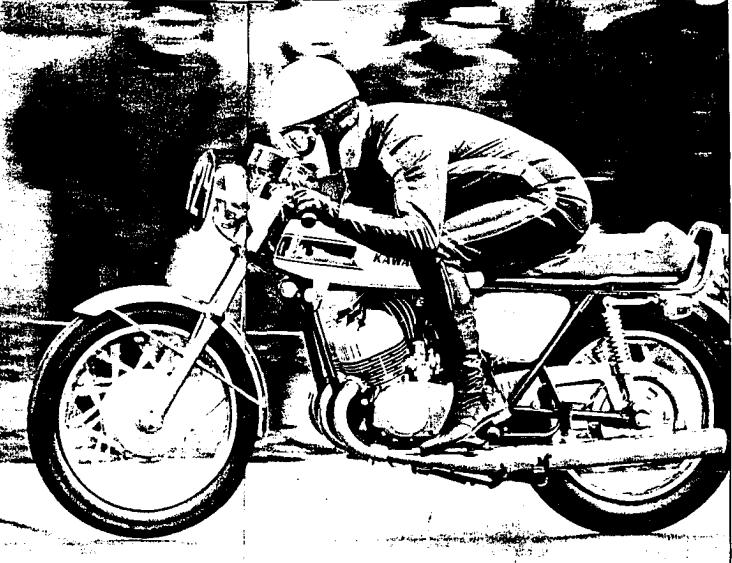

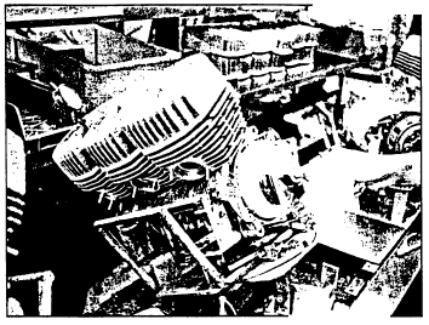

Henk Vink, Dutch

sprint champion, taking a Mach III through 400 metres in 13.48 seconds with a terminal

speed of 104.82mph, and a Mach III motor coming off the production line.

Part 1 The Early Years

Doug Perkins examines the legend of the screaming triple, and what lay behind it

It’s strange how a motorcycle’s character or charisma can change with time. Take

the Kawasaki Mach III. According to most, it

was the worst handling, most ferocious, fuel guzzling projectile ever to be blessed with

two wheels, with the rear normally following a different line from the often airborne

front. Well, here follow a few quotes from early road tests in highly regarded magazines:

1969 Cycle; ‘The frame is unusually strong, frame-flex, if it did exist, was not apparent. At Yataba test track in Japan the machine could be ridden at 125mph without shutting off, on the banking the Mach III was as stable as a thoroughbred road racer. On the flat, lowest lane, however, slight irregularities caused a slow predictable yawing.’ Also ‘the engine is slightly peaky’.

1969 Motorcycle Sport; ‘minimum non-scratch speed in top gear proved to he a mere 1500rpm and a swift response could be obtained at 3000rpm in any gear’. To be fair this road test also warns of change in traction when winding the power on, when exiting from a bend.

1970 Motorcycle Sport; ‘I had been warned to have is pointing straight if I was going to do any gear changing near peak revs. The front end would give a flick and step sideways about 6in but under perfect control, and easing the grip back, the Kawasaki goes through as though it’s on rails.’

We then move on a few years to, shall we say, more flamboyant journalism with the following extracts. ‘The fastest camel in the world’ and ‘Thanatoid’ (which apparently means creeping death), are a couple more recent comments.

The writer,

with 15 years of owning Kawasakis and a Mach III for six years, also found these comments

sometimes confusing and, in the case of pulling power from 3000rpm, I considered this to

he a misprint. However, hopefully, as the development of the Mach Ill is unfolded some

light will be shed.

The writer would hazard a guess and say that the Mach III probably

started life in 1967 as, would you believe, a 500cc disc valve two-stroke twin,

which, from photographs, is fairly obviously set in a Samurai twin frame, with the front

end borrowed from the 650cc parallel twin W2, along with a W2 rear wheel, with combined

speedo and rev counter. A second version was also built, with exposed springing, separate

speedo and tacho and different air filter box.

From this point on, no other photographs are available, so it would

seem Kawasaki decided to take the now legendary three cylinder route. The first version of

this had a yellow fuel tank with chrome plated panels, rubber knee grips and yellow side

panels, either yellow or white front guard, stainless rear and a long, approx 6in diameter

air filter housing which ran across the frame and connected directly onto the carbs. It

also sported a 3-into-2 exhaust with the centre cylinder exhaust splitting underneath the crankcases.

Version

number two looked very much like the Mach III as we know it, with a blue and white fuel

tank in pearl candy paint and silver side panels. Ceriani—type forks were also fitted

with stainless steel front and rear mudguards, chrome plated chain guard, silver headlamp

bracket and fork shrouds and what looks like the final frame with chrome plated grab rail.

The exhausts were three-into-three with one on the right and two on the left and a flat

cut off as the baffle point. The air filter housing was placed near the rear of the fuel

tank and connected to the carbs via a three-piece rubber connector.

Version

number two looked very much like the Mach III as we know it, with a blue and white fuel

tank in pearl candy paint and silver side panels. Ceriani—type forks were also fitted

with stainless steel front and rear mudguards, chrome plated chain guard, silver headlamp

bracket and fork shrouds and what looks like the final frame with chrome plated grab rail.

The exhausts were three-into-three with one on the right and two on the left and a flat

cut off as the baffle point. The air filter housing was placed near the rear of the fuel

tank and connected to the carbs via a three-piece rubber connector.

Another version of this was built which featured a three-into-four

exhaust where the centre cylinder exhaust port split into two separate exhausts at a

manifold bolted to the cylinder. The exhausts were identical on each side and in the same

position as on the eventual production model, i.e., one very low. These exhausts also

appeared to have a very shallow cone on the ends as on the production versions. The tank

colours on this last pre-production type unit were candy red with a blue band approx 50mm

wide around the edge, and a long Kawasaki emblem in black and white. There was also a red

chrome version with rubber knee grips inserted and the old style Kawasaki wing badge

screwed on. Interestingly, the speedo face was black, whereas the tacho had a white face,

with the ignition switch located in between them. It is of interest to note that on all of

these pre-production versions, the engine cases

were very highly polished, the front brake drum was black and all the lever mechanisms

were on the left of the machine whereas, apart from a very early press photograph, all

drum brake versions of the machine were as the W2, i.e., the right.

At this point I would like to stress that, in my own

personal view, Kawasaki were caught napping and not for the first time, by Honda and that

famous 750, for on the first production versions of the Mach III we had a standard front

brake, sprayed side casings and the ignition switch identical to the Samurai sited

underneath the fuel tank and not as on the prototype. What also seems strange is that

early production machines featured stainless steel exhausts and not the normal chrome

plated items, as fitted later.

At this point I would like to stress that, in my own

personal view, Kawasaki were caught napping and not for the first time, by Honda and that

famous 750, for on the first production versions of the Mach III we had a standard front

brake, sprayed side casings and the ignition switch identical to the Samurai sited

underneath the fuel tank and not as on the prototype. What also seems strange is that

early production machines featured stainless steel exhausts and not the normal chrome

plated items, as fitted later.

So, that was the Mach III in its pre-≠production form. When it did

finally appear in 1968 it certainly shook the motorcycle world as Kawasaki were claiming a

top speed of 124mph and a standing start quarter mile in 12.4 secs!

There can be no doubt, though, that the Mach III had been designed by

either an individual or committee who really felt that needs of the new generation of

motorcyclists — yes, I also hate the word ‘biker’ Mr. Eason (see MCe

letters page July 86).

The whole machine seemed to be tigerish in appearance with the

sculptured fuel tank, flat handlebars which raked slightly rearwards, the exhausts were

almost a work of art in themselves with just the right angle of upsweep to give the

impression of power, the large chrome grab rail certainly finished the job off! But it was

a subtle overall impression best likened with, say a Golf GTI as against an Astra GTE. The

only other motorcycles I rate in the same class - looking as though they do 100mph

standing still - were the Vincent 1000 and the Ducati 900SS, which I still rate as the

best looking motorcycles of all time.

There

were two colours available for the original ‘69 model. The most common had a white

fuel tank with a broad blue band stretching from the front of the tank to the knee

indents, two smaller bands approximately 6mm wide ran parallel with Kawasaki in blue

letters actually situated inside the knee indents. The side panel and oil tank were also

its white with a cast aluminum badge saying 'Mach III 500' on the side panel. This badge

was available in either white and red or blue and red. Peacock Grey was the other colour

option available but the colour was, in fact, nearer black than grey with a metallic

finish and a black instead of blue band across she tank. Headlamp bodies differed on both

machines with the Midnight White version supplied with a chrome plated unit, as against

black for the Peacock Grey option.

There

were two colours available for the original ‘69 model. The most common had a white

fuel tank with a broad blue band stretching from the front of the tank to the knee

indents, two smaller bands approximately 6mm wide ran parallel with Kawasaki in blue

letters actually situated inside the knee indents. The side panel and oil tank were also

its white with a cast aluminum badge saying 'Mach III 500' on the side panel. This badge

was available in either white and red or blue and red. Peacock Grey was the other colour

option available but the colour was, in fact, nearer black than grey with a metallic

finish and a black instead of blue band across she tank. Headlamp bodies differed on both

machines with the Midnight White version supplied with a chrome plated unit, as against

black for the Peacock Grey option.

Kawasaki was making great claims for the power unit with a guaranteed

60hp at 7500rpm from every unit. The other claim was for a revolutionary CDI system and

surface gap spark plugs eliminating fouling with an expected 5000 mile life. Some problems

were encountered with the CDI, mainly the insulation breaking down on the pick-up due to

heat build up. as well as water and oil seeping into the distributor via the wiring

harness where it ran under the carbs. Problems were also experienced in the UK as the CDI

caused havoc with television sets as it blasted by. At least Kawasaki rapidly came up with

the answer by changing to points ignition on the UK model only. This was a blessing in

disguise as those two little black boxes under the seat now cost £800 (yes, £800) plus

VAT, to replace! The surface gap spark plugs also gave problems and owners quickly

reverted to standard plugs, which normally have a life of 1000—5000 miles depending

on use.

In the second part of this feature,

we’ll see just how effectively this ‘performance guarantee’ was realized in

the hands of the owners.